By Roger W. Burdette, special to CoinWeek …..

1873 was an interesting year for the United States Mint. The most important event was the passage and implementation of the Coinage Act of 1873. This new law revised the position of our coin manufacturing department, placing it directly under the control of the Treasury Department. It also changed the Mint Bureau’s internal organization, from one controlled by a director at the Philadelphia Mint managing several subsidiary branch mints to a director located in Washington, D.C. at Treasury headquarters. All mints became independent facilities managed by a superintendent reporting to the Secretary of the Treasury, thereby removing the Philadelphia facility’s unique authority. The concept of “branch mints” was eliminated – at least in law.

James Pollock, Mint Director at Philadelphia under the old law, remained there as Superintendent, and Henry R. Linderman, Pollock’s predecessor, was appointed Director of the Mint Bureau (the United States Mint). Both men had considerable experience in running the facilities, but Linderman also had an international reputation in economics and was the preferred person for the new job.

The same Mint Act also eliminated the position of Mint Treasurer, replacing it with a Cashier, and moved certain department heads, such as Melting and Refining, from presidential appointment to normal administrative positions.

Circulating coinage was simplified by the elimination of the standard silver dollar, the half dime, the three-cent silver piece, and the two-cent bronze piece. A new dollar denomination silver coin, intended only for export, called the “Trade Dollar”, was authorized as a means of competing with the Mexican eight reales in Asian markets and providing a market for domestic silver.

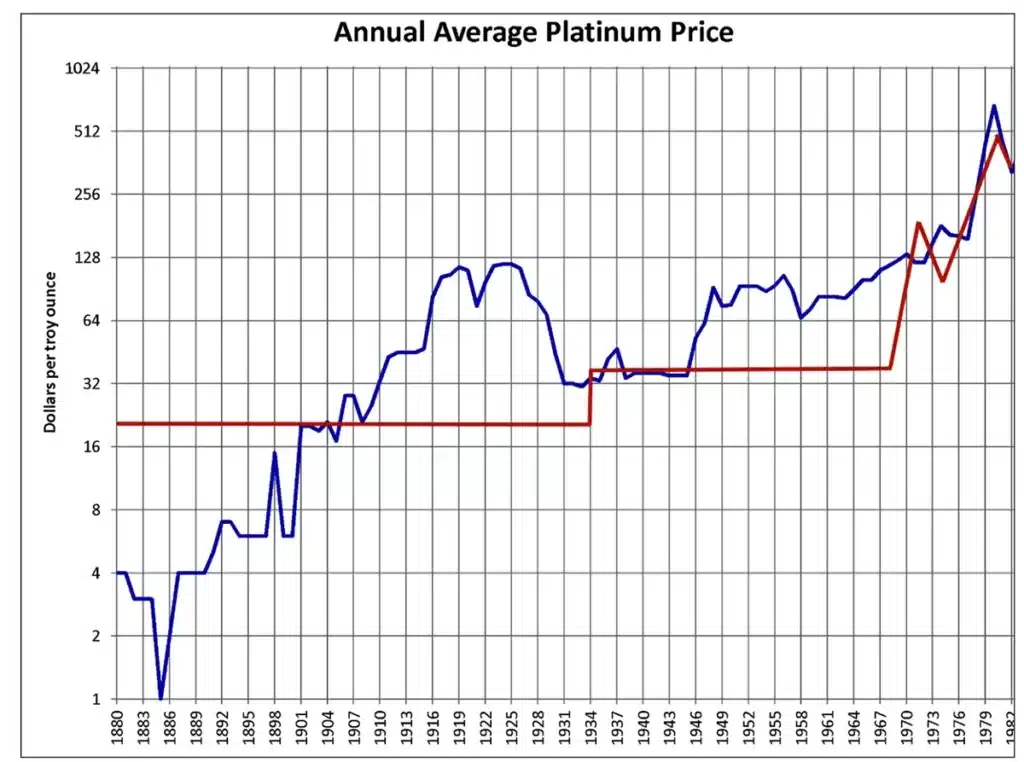

Another change brought about by the new law was a slight increase in subsidiary silver coin weights to align them with French silver coins.

This made two heavier half dollars exactly equal to one French five-franc coin weighing 25 grams. To identify heavier coins, the engraver at the Philadelphia branch of the United States Mint added arrowheads on either side of the date beginning with coins struck on and after April 1, 1873. Varieties are known with large and small arrowheads.

Although new coin weights were nominally within tolerance for the old coins, new weights for balances had to be prepared so that adjusters could separate planchets based on the new law. A telegram from Henry R. Linderman, Director Designate, to Pollock at Philadelphia said:

Please forward immediately via overland express dies for new silver coinage to San Francisco and Carson, and at your earliest convenience [the] necessary weights for adjustment of same[1].

But during the three months before the new law became active, the Mint had to produce coins for circulation and Proof sets for collectors. Annual coinage began with date punches from a slightly modified set as used in 1872 and for several previous years. We don’t have specific information about the person who prepared these, but it might have been former Mint Assistant Engraver Anthony Paquet or a digit and letter specialist in Philadelphia or New York.

Below is a comparison of the digits “187” from 1872 and the first issues of 1873.

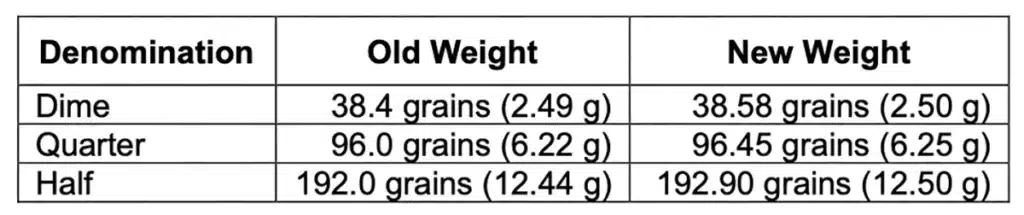

Other than possibly being spaced a little too closely together, “187” seems satisfactory and consistent with the previous year’s dates. However, if we view the full 1873 date, a problem becomes evident. The numeral “3” has large ball serifs or knobs, which gave it an appearance easily confused with the numeral “8”.

This was particularly troublesome for those with poor eyesight concerning the legibility of small-size coins such as cents, three and five-cent nickels, dimes, gold dollars, quarter eagles, and three-dollar pieces. Chief Coiner A. Loudon Snowden of the Philadelphia Mint was concerned about date legibility and wrote to Pollock in January.

Dear Sir:

I desire in a formal manner to direct your attention to the “figures” used in dating the dies for the present year.

They are so heavy, and the space between each so very small that upon the smaller gold and silver, and upon the base coins, it is almost impossible to distinguish with the naked eye, whether the last figure is an eight or a three.

In our ordinary coinage many of the pieces are not brought fully up, and upon such it is impossible to distinguish what is the last figure of this year’s date.

I do not think it creditable to the institution that the coinage of the year should be issued bearing this defect in the date.

I would recommend that an entire new set of figures, avoiding the defects of those in use, be prepared at the earliest possible day[2].

We don’t have Pollock’s reply, but it seems that Engraver William Barber, or more likely assistant William Key, set to work preparing new punches only for the digit “3”[3].

A comparison indicates the ball serifs were cut down in size without changing the digit’s body or general outline. For reasons that are unclear at present but possibly related to production quotas, dates with an open 3 were put into use on dimes, quarters, and half dollars before the introduction of arrowheads denoting the weight change on April 1. This resulted in all three subsidiary silver denominations existing in open 3 versions with and without arrowheads.

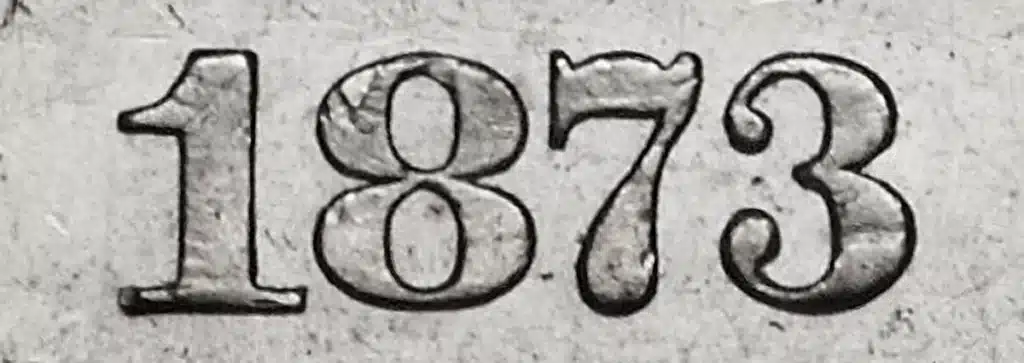

This table displays all denominations and mintage estimates produced at the Philadelphia Mint for 1873. At the beginning of 1873, all had a close 3 in the date, and those remaining in production after April 1. Gray boxes indicate no coins made.

Three variations of the 1873 date (below) were produced through at least April 1, 1873. The San Francisco and Carson City, Nevada branches of the United States Mint also struck similar combinations but in much smaller quantities.

During research for this column, the author attempted to determine if open 3, no arrowhead silver coins followed the old weight standard. Unfortunately, most high-grade specimens seem to be locked in plastic slabs, making their weights inaccessible. Further, old records from ANACS when it was owned by the American Numismatic Association, which might have included these data, seem to be lost[4].

Except for adding arrowheads next to the date, close and open 3s are possibly the most distinctive features of 1873 coinage, and are responsible for more date versions than in any other series of coins produced by the United States Mint.

* * *

Notes

[1] RG104 E-1 Box 91. Telegram dated March 21, 1873 to Pollock from Linderman.

[2] RG104 E-1 Box 91. Letter dated January 18, 1873 to Pollock from Snowden.

[3] Assistant Key was relegated to preparing ornamental wreaths, lettering master dies, and preparing logo punches. He prepared single punches for the motto IN GOD WE TRUST used on George T. Morgan’s half dollar and dollar patterns, and similar work for William Barber’s patterns in 1877-78.

[4] Numismatist Tom DeLorey, writing in a message dated September 16, 2023, comments: “The early ANACS submission forms included very accurate weights partly for identification purposes, but those records are lost.” PCGS Coin Forum, thread titled “Does anybody have Precise Weights of 1873 No Arrows Silver Dimes, Quarters and Halves?” Mr. DeLorey and Dan Owens also examined the situation of 700 silver dollars reported delivered by the San Francisco Mint in 1783. Their conclusion was that the coins had been struck and dated in 1872 and merely delivered the next calendar year. Also, any 1873-S silver dollars would have used the same 1872-style numerals as seen in Philadelphia silver dollars. See: “Not a Ghost of a Chance,” The Numismatist. July 2019. Pages 30-41.

* * *

The post 1873 : The Year That Changed the United States Mint appeared first on CoinWeek: Rare Coin, Currency, and Bullion News for Collectors.